—

I still love the 20th century

Richard ARTSCHWAGER, Daniel BUREN, James Lee BYARS, Cerith Wyn EVANS, Peter FEND, Poul GERNES, Dan GRAHAM, Jon KESSLER, Arthur KÖPCKE, Stanislav KOLIBAL, Wili KOPF, Thomas LOCHER, Rupert S. LOVEJOY, Gerhard MERZ, Rune MIELDS, Matt MULLICAN, Paul OUTERBRIDGE jun., Blinky PALERMO, Leon POLK SMITH, Arnulf RAINER, Ad REINHARDT, Gerhard RICHTER, Wilhelm SASNAL, Robert SMITHSON, Mike/Doug STARN, Herwig TURK/Günter STÖGER

James Lee Byars minimalist paper collage “I still love the 20th century” from the late 1970s testifies to his keen interest in the notion of ephemerality, as well as its coexistence. Meticulously folded black silk paper on which he leaves traces of his own transiency by using a tender silver crayon is reminiscent of his own elusive existence. For all its fragility, the work asserts a “claim to eternity” by having the artist proclaim I still love the 20th century, referring to a period of time not yet completed.

The eponymous group show does not intend to provide an overview of the most significant art-historical tendencies of the 20th century— as one can observe at numerous contemporary art exhibitions that have all but scratched the surface in their attempts to probe into the depths of art. This show is not a wistful reminiscence of times gone by.

Rather, it regards itself as a critical commentary on the current art scene in which it is no longer the work itself and its genesis, but commercial success that seems to be the new yardstick for prosperity. As a consequence of art transforming into a mundane form of investment people seem to have lost their personal relationship with it. The artwork is reduced to a decorative status symbol. People buy brands whose value is artificially driven upwards. The reasons for the current art boom can be traced back to the past century. Already in the 1990s a heated debate about “information highways” revolved around the visions and impact of information societies. On the one hand for a large part of society information becomes accessible in ever faster ways and on the other hand it also becomes liable to be interchangeable and to be manipulated much easier. The enhanced global network of our society and simplification of access to the market thanks to technological progress in the information, communication, transport, and capital have contributed to a globalisation of the art market. There is a tendency towards big shows, as proved by innumerable biennials, triennials, and art fairs. They inundate viewers with “newcomers” and “stars” and leave them with the unpleasant sensation of having missed out on a trend or an important event altogether.

With reference to the “accelerating” tradition of fairs and exhibitions that has developed over time the group show I still love the 20th century is designed to scrutinise this system. Even though a gallery run as a soleyly private business can never fully disregard the laws of economics, its primordial task is to promote and partake in artists’ development by engaging in an ongoing dialog with them, as well as to raise public cultural awareness, to educate and familiarise people about art and art history.

This show focuses on works such as studies or models that illustrate the evolution of artistic forms of expression and contexts and thus serve as important documents. Gerhard Richter’s work Untitled (1979), for example, is one of just three detailed studies relating to his monumental works 451 and 452 (two yellow strokes) and in addition to his true-to-scale sketch Strich is considered a crucial early work on his way towards abstraction.

It is only in combination with the watercolor sketch carefully applied to graph paper that the viewer is able to identify the exact composition of the two shaped canvases by Gerhard Merz (1978) and to experience how much his concept of painting is determined by architectural thinking.

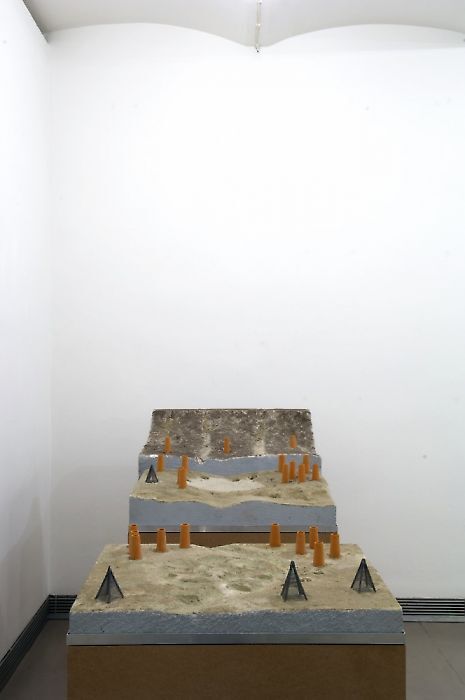

The overall space of the gallery —extending across three levels—provides for a different spatial perception. By deliberately staging the art on display, perception is decelerated as new connections and associations are triggered by aesthetic points of reference. With his mirror installations and buildings linking architecture and sculpture, Dan Graham addresses the relations between perception and being perceived. All three models of his pavilions shown in the exhibition were accomplished years later. With their mirrored or transparent panels they express the viewers process of perception, his interaction with the environment and awareness to his own body.

The video on display in the last exhibition room by Herwig Turk and Günter Stöger, shot in the Utah salt desert in 2005, raises questions about the status of individuals embedded in their spatial and social environment. Throughout the 28 minute video the movements of the picture and figures generate a flow of constantly changing landscapes and horizons. For the viewer, lying on a salt-covered ground, it is often impossible to disentangle the different levels of space and perception.

curator/text: Fiona Liewehr

Inquiry

Please leave your message below.