—

Waters and Watercolours

Martin Dammann, Berta Fischer, Chris Johanson, Herwig Kempinger, Amélia Toledo, John Waters, Peter Zimmermann

My photographs are little films, narratives like storyboards. It's like being in the editing room. You take found material and transform it into something else. (John Waters)

In the 1990ies John Waters – originally the celebrated "Trash Auteur" of underground cinema – developed a passion for photography. With a kind of "high-art concept" in mind, he looked for raw material in video tapes and his own reels of film out of which, by editing and cutting, he composed new small-scale photo movies. Instead of high- definition 35mm film frames, Waters created reproductions diluted by two rounds of photographic translation. They are blurred, coarse-grained and broken down into pixels. They pretend to tell the storyline of a movie but the narrative gets lost somewhere in the process of reproduction and recomposition. As we look for content, trying to track it down, potential meanings arise, enabling beholders to fill gaps via their own idiosyncratic emotional and intellectual background.

Waters and Watercolours is a caleidoscopic narrative attempting to relate potential meanings and interpretations of water and colour; it deals with cemented categories of art history, expanding them towards FUZZINESS, DEPTH OF FOCUS, FLOWING TRANSITIONS/SUPERIMPOSITION, MOVEMENT, FLEETINGNESS, DISSOLUTION via form, narrative and associations. The undogmatic but also incongruent combination of seven different artistic positions creates a kind of "little film” (water colours story) which leaves individual leeway for drifting around in the contexts.

When Martin Dammann calls his large watercolours "reconstructions", he describes an attempt to represent a kind of "topography of emotions" in photography by using pigment. His watercolours are based on pictures from a London photo archive specialising in private war photography. According to Dammann, photographs and what emerges from them are always subject to speculation. One can hardly determine why pictures are taken – still, the bottom line is that they must have had direct meaning at one point. Without trying to formulate "an interpretation ex cathedra" Dammann tries to decipher potential states by using the specific nature of watercolour pigment, highlighting and changing details such as outlines, faces, gestures in colours. The impression of randomness that arises is by no means unintentional; after all, the resulting leeway for associations (similar to John Waters' photo films) is merely meant to reconstruct the fiction of potential states.

Like Martin Dammann, Peter Zimmermann also falls back on an archive of collected visual motifs. He changes scanned details from his own works as well as found pictures from the Internet, from television and other information sources on his computer in a targeted way, to such an extent that even the faintest notion of an effigy turns out to be imaginary. On the basis of the computer-generated picture, the artist then defines surface areas which he casts in epoxy resin in a step-by-step process. The resulting flowing forms, the materiality of the paint emerging for example when the pigments create unintended streaks, and the impression of depth of focus caused by superimposed layers of pigment suggest that his works are visually akin to watercolours.

Not only can the process of transformation from original to painted picture be described as "flowing", the potential of permanent changeability also points to a "FLOW" inherent in the pictures. Chris Johanson hardly considers the scientific/theoretical notion of a FLOW when he directs his thoughts (artistic intentions) to water and colour, that which is immanently flowing and unfocusable. "...the people on earth are becoming more frightenend. They are trying to hide in fantasy, in drugs, in running. We are running around buying things, we are chickens with our heads cut off. (...) Even the water and weather are going crazy now more than ever. Only time will tell if it will subside and mellow out. Who knows, now that the government have upped the ante. Who knows." (Chris Johanson) Johanson's approach to the art world is one of a deliberate outsider with a characteristically odd yet perspicacious and critical view of existing societal systems. Using simple materials (paper and wooden panels), he makes his mark by applying a visual language reminiscent of graffiti and comic strips. Deliberately dilettantic, he denies illusionist space, translating ambivalent states (anxieties, compulsions, obsessions, isolation...) into visual worlds that draw the beholder's attention on the "FLOW" of the commonplace.

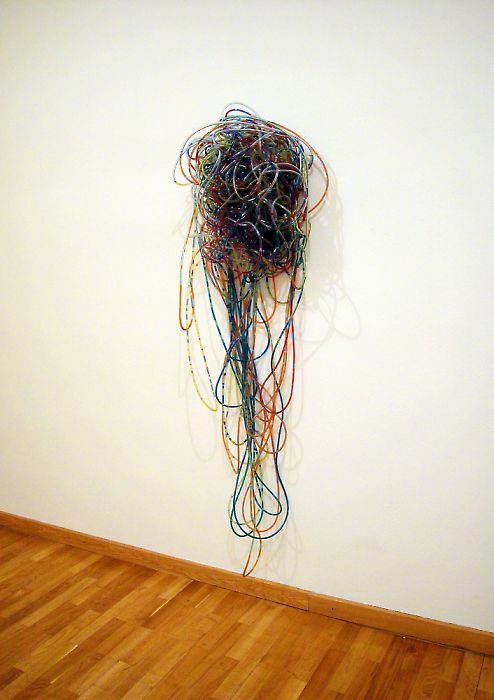

The fact that the notion of the watercolour may progress from painting to three-dimensionality is reflected in the works of Berta Fischer and Amélia Toledo. The neon-coloured acrylic glass sculptures by Berta Fischer are suspended in space in the style of écriture automatique (an innovation contributed to art by Surrealism). Hanging from near-invisible nylon threads, a kind of drawing in space materialises, with lines that are lost in transparency in spite of the rigidity of the material. The sculptures that emerge are imaginary reflections of quick impulses, visualising thought-up, transitory movement in space; the amorphous shapes do not seek to transport narrative content, they are discreet messages suggesting fleetingness and disintegration while still expressing the richness of the imaginary. Compacting shapes in space, reducing and dissolving them, these works create room for association in which painterly poetics unfold without requiring painting per se. When Amélia Toledo deals with Medusa's head, a wide-spread motif in art history, by interpreting and appropriating natural and artificial substances, she seeks to communicate that there is leeway for associations reflecting "the nature of the artificial". The serpent-covered head, "a sight so dreadful it petrifies the beholder", is condensed in a tangle of transparent plastic hoses filled with a mixture of water, oil and pigment, thus conveying a state of immanent movement and animation in visual terms. Materiality and colour in space and time form the basis of Amélia Toledo's oeuvre. She develops her artistic strategy as she searches for and brings together transitory values inherent in the objects around us – narrative messages (as found in Medusa's head) are solely transported via the specific characteristics of individual substances, their combination and confrontation.

"If it were actually possible to create a sculpture without any clear delineation in space, I'd probably do that. However, technically it isn't possible yet.“ (Herwig Kempinger) Herwig Kempinger's most recent photographic works are a complete denial of materiality; thus, they logically continue along the lines of his earlier explorations of immaterial objects as they pass into transitoriness. "Temporary volumes" is what he calls the three-dimensional constellations which give permanent (i.e. photographic) shape to continuously changing, vanishing and re-appearing forms. Kempinger succeeds in making his notion of "ideal sculpture“ materialise by means of photography - the impression of three-dimensionality in fleeting clear outlines. "Construction sites are temporary volumes, too; they affect us in a way in which the buildings that will be taking their place for decades hardly ever impact us." (Herwig Kempinger) The series of watercolours showing construction sites is a radical (visual) denial of watercolour, of transitory, constantly changing and dissolving space. The focused gaze, the sharp lines and extreme contrasts result in an ambivalent atmosphere lending photographic presence to the watercolours. However, the extreme compactness of light and pigment causes the empty spaces to become structural elements that hint at the grey area between fact and fiction, a temporary mise-en-scène and its disintegration.

Text: Ilse Lafer

Inquiry

Please leave your message below.