—

John Waters

John Waters, who William S. Borroughs once called the “Pope of Trash,” has attained controversial fame as a provocative film director. His themes––sex, religion and social exclusion––are usually ignored by bourgeois society.(1)

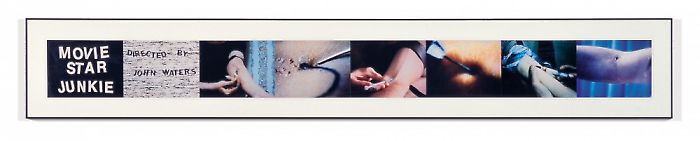

[…] In trying to trace the genesis of his first “serious” photograph, Waters recalls receiving a request for a specific film still from Multiple Maniacs (1970). And though he vividly “remembered Divine’s face in the one moment between rape and miraclulous intervention where he lived up to the spiritual side of his name,” (2) there was no photograph of it. So Waters decided to make the film-still himself. […] The result, Divine in Ecstasy (1992), is hilarious and harrowing. [Thenceforth he] made more photographic sequences of stills—extracted from his own movies, and even more willfully from those made by others—that were essential for the stories he wanted to see, remember, and tell to himself.

[…] The pictures he makes have an odd beauty about them. Instead of the crisp pictures that 35 mm film delivers, Water’s images have already been degraded through two previous rounds of photographic translation: from film to television, and from television to snapshot. They’re grainy and pixilated. Some look like tapestries that have been woven with the elegantly striated scanning lines that Waters’s camera reads off the television screen. Individual frames—photographed from videotapes of wide-screen movies radically cropped to fit the squarish format of television screens—have a compressed, jewel-like quality about them.

[…] Waters’s relationship to photography, like his relationship to mainstream film, is largely defined by his outsider status and his characteristically oblique but incisive point of view. He’s an irreverent but clear-eyed intruder, a filmmaker who has stepped over a border into another disciplinary realm. It is through the process of carving out an interstitial space for himself, a no-man’s-land between film and photography, that Waters has found another avenue for expression. With no rules to follow and no allegiances or constituencies to be maintained, he takes whatever he needs from the historic arsenals of film and photographic techniques. […]

(1) Editor’s note

(2) John Waters, Director’s Cut (Zurich and New York: Scalo, 1997), p. 283.

Marvin Heiferman, “Everything Always Looks Good Through Here! John Waters and Photography,” in: John Waters: Change of Life, New Museum of Contemporary Art, Harry N. Abrams Inc, New York, 2004, pp. 20-41.

Inquiry

Please leave your message below.