—

Andreas Fogarasi

[scene missing]

Manon de Boer, Cerith Wyn Evans, Andreas Fogarasi, Björn Kämmerer, Theo Ligthart, Ján Mancuska, Christian Mayer, Wolfgang Plöger, Nadim Vardag, Marijke van Warmerdam, Christoph Weber

The exhibition [scene missing] groups eleven recent artistic positions that engage with cinema and film. Without showing film in the usual sense or simulating cinematic situations, the works presented here all interrogate methods of narrative construction and point out the fragmentary character of reality and its filmic representation. The absence of cinema and film at the exhibition [scene missing] is a product of our collective film memory. The receiver completes "the scene missing” by taking recourse to his or her own memories of cinema and film history. In the field of tension between the black box and the white cube, the cinema becomes a material in the works exhibited.

In contrast to avant-garde film and the expanded cinema, the motivation behind this artistic practice is not breaking with standard conventions, but rather the appropriation of such conventions. The conventions of filmic representation provide a starting point. Narrative structures, an interest in the mechanics of the projection apparatus, cinematographic traditions and the reception of film are all subjected to deconstruction and recoding. Film history becomes raw material.

Björn Kämmerer, Marijke van Warmerdam, Manon de Boer and Christoph Weber share a common interest. They make use of antiquated technology, forcing onto film projectors or old tape players functions for which they were not intended. The mechanical apparatus is staged as fetish.

In his 35mm film loop escalator (2006), the German artist Björn Kämmerer shows a boy dressed in coat and tie walking up and down a stairway, apparently endlessly. The linear narrative structure and spatial orientation is suspended by the editing and reflection and generates a disturbing sense of infinitude.

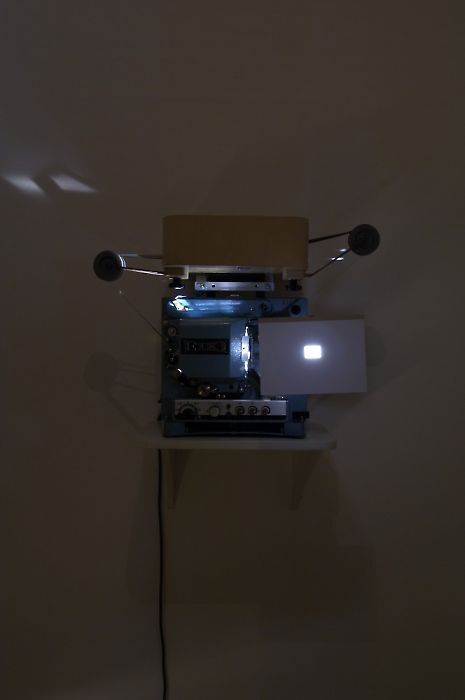

The 16mm film loop Passage (1992) by the Dutch artist Marijke van Warmerdam shows a black small square that slowly emerges from the middle of a white backdrop to fill the entire projection surface; after the process has completed, it then starts again. This perpetual motion engenders associations in the spectator that can allow stories to develop. As the artist puts it, “Passage is a work which troubles my eye and my thoughts. I have the feeling that the phenomenon film has been stripped to the bone, but still someone is pulling my leg. In the meantime, my eye is very much attracted by its movements in black and white. It could be a tunnel, it could be an elevator, it could be the beginning of a story. In fact, it is no more than what it is. Or isn't it?"

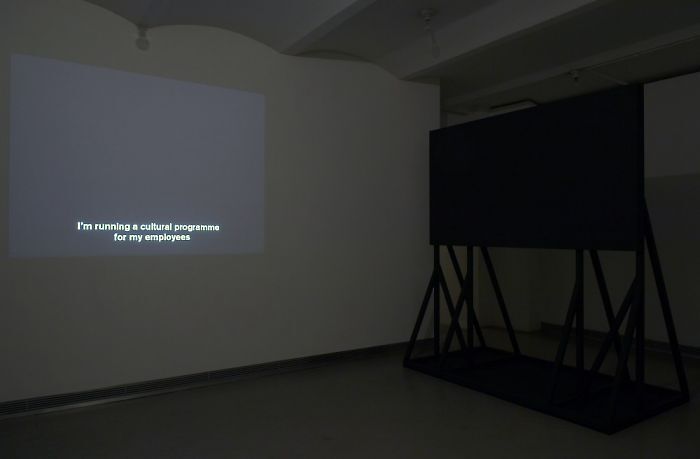

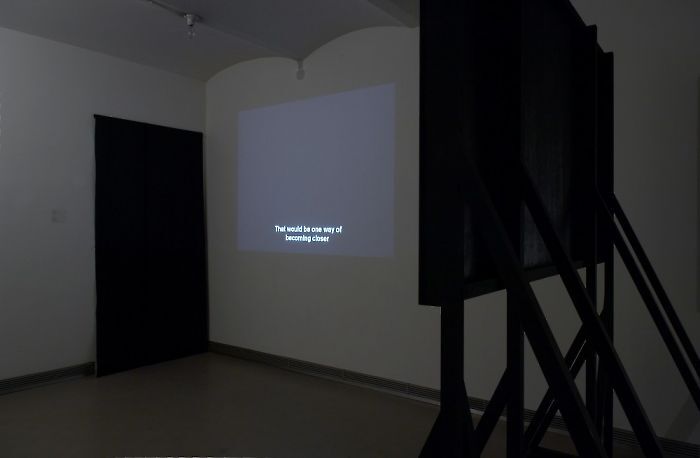

Nadim Vardag explores the construction of mediated images and questions the mechanisms of cinema and film production using quite diverse media: sculpture, drawing, and film. In the work The Night (2005) Vardag uses the subtitles from the Antonioni film of the same name. The absence of image and sound places the focus on the written dialogue. The screenplay seems to return as the starting point for making a film, serving as material for the viewer to imagine a film of his or her own: beholder becomes director. Similarly, Black Screen (2007) challenges us to fill the void black screen with our own individual projections. This sculptural work represents the mimetic depiction of a surface of projection: dysfunctional due to its being black, it remains empty and imageless. At the same time, the work also recalls minimalist sculpture and functions as a projection surface for our own cinema memories.

In this work Avant-Garde (Rainer, Kubelka, Ligthart) (2002) Theo Ligthart analyzes an icon of avant-garde film: Peter Kubelka's film Arnulf Rainer (1960). Rainer had commissioned Kubelka to produce a documentary on his artistic work; to Rainer’s surprise, Kubelka then presented him with a film consisting exclusively of white and black squares in a rhythmic sequence that was subject to a strict score. Ligthart translates this score in his work Avant-Garde (Rainer, Kubelka, Ligthart) to a rhythm of light and dark by synchronizing the supply of electricity supply for a light source according to the score of Kubelka’s film, using a small box with a processor to control the flow of electricity. This box can be attached to any random light source, allowing any living room to be transformed into an avant-garde cinema. His work Spielfilm (Director’s Cut) (2002-2004) shown in the gallery skylight hall is formally based on the visual language of avant-garde film. The break with filmic narration in experimental cinema is here taken to its absurd limit; plots from mainstream cinema are all combined into a single sentence and presented in a formal reproduction of a cinema advertising case, thus referring to the aesthetic of film stills as shown in such displays in Central Europe. The result is a sequence of text images that displays the redundancy of the standard narrative cinema in an ironic way and directly inspires the individual film memory of the receiver.

In end (2007) and 1974, 1975, 1976... (2007), Andreas Fogarasi presents monumental silk screens of the intertitles from his video installation Kultur und Freizeit (2006), which was on view at the last Venice Biennale. The size of the works corresponds to the projection surface of his video. The film deals with cultural and educational institutions in Budapest, their architecture and the change in programming and questions about the aesthetic and structural notions of their builders and users. The intertitles, which originally point to the former and current realities of architectures presented, are extracted from the videos. Now robbed of their context, they become projection surfaces for individual memories.

In his installation untitled (one, two flags) (2008), the German artist Wolfgang Plöger shows two slide projections of rooftop landscapes; between the two he has placed a flag being blown by a fan. The static projections are animated by the moving shadow of the flattering flag; the motionless image seems to become cinematic. Shadow theater fuses with realistic photography, forming a poetic installation. The link of the real, present object of the flag and the unreal roof landscape pose the question of the representation of reality by the cinematographic apparatus and the perception of reality linked to it.

The installation Sorry Being So Late (2007) by Czech artist Ján Mancuska is based on photographs taken in Prague’s largest park, just near the artist’s home. Over the map of the park, he placed a grid, and walked from sunrise to sunset from one of the sixty-four points on the grid to another, shooting photographs from each point of intersection. Thus, each roll of film hanging from the ceiling marks a grid point and the perspectives of the park that can be seen from there. The work documents the entire area of the park and its change in daylight. Presented in front of an oversized light box, the beholder can take up the spatial as well as temporal sequence of the park and the course of the day, but in a fully different space and time relationship. By choosing the points of intersection as a camera position, the entire landscape seems to be documented, but these very points of intersection become the blind spots in the park’s documentation. The hanging rolls of film stand for the lack of depictions of the sites from which the park was photographed.

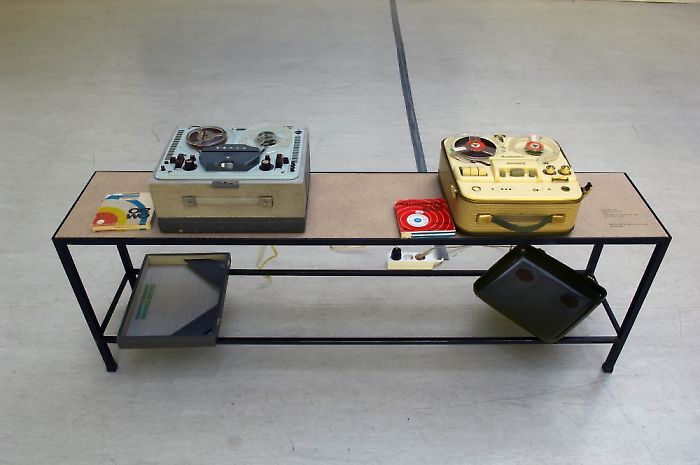

In Christoph Weber’s work Telefunken und Tesla (2007) two tape recorders from the late 1950s (a West German Telefunken and a Czechoslovakian Tesla) — enter into an apparent dialogue with one another. The machines play back fragments of a text compiled of fragments from German versions of various science fiction films from the 1950s to today. They enter into a fictive dialogue that represents in an emotionally dramatic fashion the scientifically charged propaganda battles of the Cold War in a television spaceship. By contrasting two devices from the early days of home recording, the artist refers to a time when the propaganda battle between east and west was at its climax and found its way into household archives through such media.

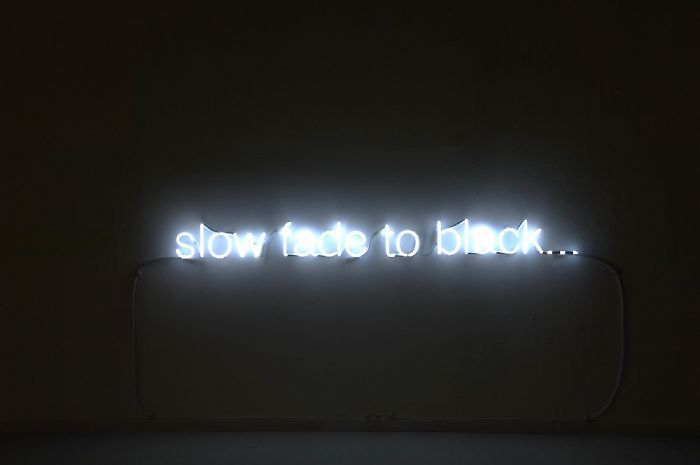

Since the early 1990s, Welsh artist Cerith Wyn Evans has been combining multilayered references from literature, poetry, philosophy, film theory, and the modern natural sciences with formal allusions to the conceptual models of the art work from the 1960s and 1970s in his work. In expansive installations—light writing on walls, film projections, and sculptural objects—Wyn Evans thus evokes an aesthetic cosmos in which the unending process of subjective and associative perception takes the place of clarity and transparency in conveying information. The work exhibited here slow fade to black… (reversed) (2004) comes from the artist’s Subtitle Series. The spatial placement of the neon lighting close to the floor transforms the gallery’s white wall into a film-like image. But the content of the sentence contrasts with the garish neon light and bright walls; slow fade to black suggests the slow disappearance of the image, whereby this expectation is constantly disappointed.

For the Indian born artist Manon de Boer, history is not a linear series of events but the experience of a constant process in which selective memories are set in relation to one another in a very particular way. Using the personal story as a narrative method, Boer explores the relationship between language, time, and the claim to truth in her work. The “narrative history” of key figures from various contexts, like Sylvia Kristel, who achieved some fame as the actress Emanuelle, allows the artist to explore concepts of memory and conviction and the coincidence of lived and written history in general. Sylvia, March 1&2, 2001 Hollywood Hills (2001) shows a close up of Sylvia Kristel looking into the camera and smoking. The rattling sound of the 16mm projector becomes the sound track of the silent dialogue between the figure represented and the artist. The tradition of portraiture is thus linked to individual filmic memory.

Christian Mayer’s film Sherlock Jr. (Buster Keaton, 1924) will be shown as a film supporting the regular program at Top Kino in the framework of the exhibition [scene missing]—a supporting film that does entirely without images. In this film, a scene from the Buster Keaton film Sherlock Jr. is described in the fashion of the running commentary that is provided for the blind or vision-impaired. While the film projector only projects white light on the screen, a voice describes how Keaton springs through a cinema screen into a film, where as an active figure he tumbles into a whole series of calamities, for he refuses to understand the discontinuity of time and space in film. By replacing the original filmic image with an oral narrative, this sound film expands the complex architecture of Keaton’s film into the viewing space. The narrative places the story directly in our imagination and allows us to imagine a space where fiction and reality can no longer be distinguished from one another.

Text / Curator: Fiona Liewehr

Biography

1977 born in Vienna, lives and works in Vienna

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2026

Fábrica de Ossos, Lehmann Contemporary, Porto

Raising Flags, museum in progress, Vienna

2025

City of Glass, tranzit.ro/Cluj, Romania

Weinstadt, Bierstadt, Wasserstadt, Lombardi—Kargl, Vienna

Cittá d'Acciaio, Galleria Massimo Ligreggi, Catania

2024

Cities, Gandy Gallery, Bratislava

2023

Figur, Kunstfenster Gnas, Gnas

Kyiv, Brussels, Budapest, Vintage Galéria, Budapest

Last Minutes, Kunsthaus Muerz, Mürzzuschlag (wit Markéta Othová)

Letting Do, Torula Artspace, Györ (with Adrienn Kiss)

1978, QUARTZ STUDIO, Turin

2028, vai - Vorarlberger Architektur Institut, Dornbirn

2022

Skin Calender, Budapest Gallery, Budapest

Five Ways of Telling Time, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna (with Mariana Castillo Deball)

2021

Up and Down, Vi Per Gallery, Prague

2020

MI, Vintage Galérie, Budapest (with Christian Kosmas Mayer)

2019

Nine Buildings, Stripped, Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna

Work, Galería Casado Santapau, Madrid

Vasarely Go Home, Galerie Florence Loewy, Paris

Kultur und Freizeit, Per Albin, Vienna (with Christoph Ruckhäberle)

2018

Production, FL Gallery, Milan

Kettő / Two, Vintage Galéria, Budapest

Monuments offerts, Galerie Thomas Bernard / Cortex Athletico, Paris

Black Concrete, Kunstforum Montafon, Schruns (with Martina Steckholzer)

2017

Culture and Free Time, Csili Cultural Center, Budapest

Exhibition/s, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna

Plan, Galéria mesta Bratislavy/Bratislava City Gallery, Bratislava

Copy, Kunstbuero, Vienna

2016

Sculpture, Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City

Book Launch, LAMOA - Los Angeles Museum of Art, Los Angeles

Modelle, Jesuitenfoyer, Vienna

2015

Installation, Tranzit, Iași (Rumania)

Video, Galería Casado Santapau, Madrid

Photography, amt _ project, Bratislava

Tracks and Traces, City Museum, Belgrade (with Sasa Tkacenko)

2014

Black Earth, MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles (mit Oscar Tuazon)

Vasarely Go Home, GFZK – Museum of Contemporary Art, Leipzig

Vasarely Go Home, Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich

1988, Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

2013

Année Le Nôtre, Galerie Cortex Athletico, Paris

Kiosk (Buda), Park Galéria, Budapest

Kiosk (Buda), Georg Kargl Permanent, Viennaa

2012

2018, Prefix Institute of Contemporary Art, Toronto

180°, Neuer Kunstverein Wien, Vienna (with Mladen Bizumic)

Vasarely Go Home, Trafó, Budapest

Vasarely Go Home, Galerie Cortex Athletico, Bordeaux

Épitészet / Architecture, Liget Galéria, Budapest

Headlines and Small Print, Galerija Nova, Zagreb (with Maryam Jafri)

2011

La Ciudad de Color / Vasarely Go Home, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid

Constructing / Dismantling, Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Sevilla

Solo presentation, Galerie Cortex Athletico, Armory Show, New York

2010

Georgetown, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna

1998, Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Aachen

2008

Fairview, Lombard-Freid Projects, New York

Support Surface, Galerie Cortex Athletico, Bordeaux

2008, MAK, Vienna

Információ, Ernst Museum, Budapest

Kultur und Freizeit, Grazer Kunstverein, Graz

2007

Kultur und Freizeit, Hungarian Pavilion, 52. Biennale di Venezia, Venice

2006

Norden, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna

2005

Westen (aka Osten), Grazer Kunstverein, Graz

Süden, Porschehof/Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg

2004

A ist der Name für ein Modell / Étrangement proche, Liget Galéria, Budapest

2003

ABCity (The Player), Trafó, Budapest (curator)

Welcome to Regions, Display Gallery, Prague

A ist der Name für ein Modell / Étrangement proche, Offspace, Vienna

2002

Kultúrapark, Stúdió Galéria, Budapest

Culture Park, Galerie 5020, Salzburg

1999

Modell Ambient (Bunte Laune), Transit VZW, Mechelen

Selected Group Exhibitions

2026

Fragile Balance (Danger), Trafó Gallery, Budapest

THE MATERIAL SHOW, MQ Freiraum, Vienna

2025

Il Cerchio Schiacciato – nel tempo della Globalizzazione e degli Equilibri Instabili, Fondazione Mudima, Milan

Zwischen Stufen, Phasen, Stopps (TUN FÜR TUN), Kunstverein Eisenstadt, Eisenstadt

Between Spheres,Art and Science – Works from the Collection of the Central Bank of Hungary (MNB), Várkert Bazár – Ybl6 Art Space, Budapest

2024

Clubs der Zukunft | Clubs of the future, Kunstverein am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, Berlin

Loose Ends, Modest Common, Los Angeles

Täterätää! Back with a Bang! KEX Reopens, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna

2023

Handle with Care, Ludwig Museum, Budapest

Coincidence of Wants, Wien Museum MUSA, Vienna

Humans and Demons, Steirischer Herbst, Graz

Schau...9, Kunsthaus Kollitsch, Klagenfurt

Here and Now II - Vienna Sculpture 2022, Neuer Kunstverein Wien, Vienna

Wir legen alles Geld zusammen, Kunstverein Schattendorf, Schattendorf

Verzweigt. Bäume in Fotografien der Sammlung SpallArt, Städtische Galerie Rosenheim, Rosenheim

Spectacular City, Holocaust Memorial Center, Budapest

2022

On/Off the Grid, Jecza Gallery, Timisoara

Wiener Freiheit, Galerie 3, Klagenfurt

I Had a Dog and a Cat, curated by Hana Ostan Ozbolt, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna

Lost in Space, Raum, Ding und Figur – Entwicklungen innerhalb der Skulptur seit 1945, Museum Liaunig, Neuhaus/Suha

2021

CELOK JE MENŠÍ AKO SÚČET JEHO ČASTÍ, City Gallery Bratislava, Bratislava

Mäusebunker & Hygieneinstitut. Experimental Setup BERLIN Architetture di G+M Hänska I Fehling + Gogel, Sala Espositivo Gino Valle, Venice

Haus Wien, Vienna

Zwischen den Dingen, Volkskundemuseum, Vienna

PROSTESTFormen, www.paraflows.at (online)

Frech und Frei, MAK - Museum für Angewandte Kunst Wien, Vienna

SHOWING STYRIA: what will be. Towards the Plurality of Futures, STEIERMARKSCHAU / Kunst Haus Graz, Graz

2020

Would You Be Available…, Georg Kargl Permanent, Vienna

Gallery for Peace, Umetnostna galerija Maribor

Trafó Galéria, Budapest

2019

40.000 Ein Museum der Neugier, 14. Fellbach Triennale, Fellbach

Im Raum die Zeit lesen, MUMOK, Vienna

Iparterv 50+, Ludwig Museum, Budapest

Presencia lúcida, Colección ESPAC, Mexico City

Hommage à 1969, Vasarely Museum, Budapest

Panel, MODEM, Debrecen

Textus Ex Machina, aqb Project Space, Budapest

2018

para inglês ver, Post Ford Palace, Porto

Into the City, Museum Moderner Kunst Kärnten, Klagenfurt

Universe of Relations, ZARYA Center for Contemporary Art, Vladivostok

Seeing artists voices, Metro, Porto

Stúdió’18 - Szalon, Hungarian University of Fine Arts, Budapest

Reduction, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna

Ist Eros der eben jetzt von mir beobachtete Planet?, Kunstverein am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, Berlin

2017

Wanderings, Galeria Cristina Guerra, Lisbon

Traces of Time, Leopold Museum, Vienna

OFF Biennale, Budapest

Gazdálkodj okosan! / Economize!, Ludwig Museum, Budapest

Ice Floe – The institutional issue, National Museum for the Visual Arts, Montevideo

Abstract Hungary, Künstlerhaus Halle für Kunst & Medien, Graz

10 years old, Fondazione Fotografia Modena, Modena

Save As... – What Will Remain of New Media Art?, Ludwig Museum, Budapest

LAMOA presents: Mülheim/Ruhr und die 1970er-Jahre, Kunstmuseum Mülheim an der Ruhr

moi non moi, Wiener Art Foundation in Athens, Athens

2016

The Errors of Beauty, National Gallery, Sofia

The Language of Things – Material Hi/Stories from the Collection, 21er Haus, Vienna

Grenzen der Geste, Galerie der Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst, Leipzig

The Past is the Past, Galerie Thomas Bernard / Cortex Athletico, Paris

Cartography of Artist Solidarity, tranzit.hu, Budapest

Art Capital, Müvészet Malom, Szentendre (Hungary)

2015

Destination Vienna, Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna

Nadezhda – The Hope Principle, special project for the 6th Moscow Biennial, Moskow

Wohin gehen wir? Videokunst zur Stadtgesellschaft, Motorenhalle, Dresden

Transparency, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna

Inside Out - Not So White Cube, Mestna Galerija, Ljubljana

Sector 17, Galerie Martin Janda, Vienna

[ ], Schwarzwaldallee, Basel

Close Up, etc. galerie, Prague

El Presente en el Pasado, Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Sevilla

Vienna Biennale – 24/7. the human condition, MAK, Vienna

Der Raum nach dem Raum, kunsthaus muerz, Mürzzuschlag

2014

I Know Not to Know, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna

El Teatro del Mundo, Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City

Report on the Construction of a Spaceship Module, New Museum, New York

Turning Points, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest

Notes from Underground, Baba Vasa’s Cellar, Shabla (Bulgaria)

Frisch eingetroffen – Neuankäufe Fotografie, Landesgalerie Linz des OÖ. Landesmuseums, Linz

Texte in der Kunst, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna

Urbane Perspektiven - Dark City, Schafhof - Europäisches Künstlerhaus Oberbayern, Freising

Interieurs, Landesgalerie Linz des OÖ. Landesmuseums, Linz

2013

Word+Work, Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder, Vienna

Jetztzeit (El tiempo del ahora), Centre d’Art la Panera, Lleida (Spain)

Modern Architecture Works, Vivacom Arthall, Sofia

Cinematic Scope, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna

De belles sculptures contemporaines – la collection du Frac des Pays de la Loire, Hab Galerie, Nantes

Conceptualism Today – Conceptual Art in Hungary since the beginning of the 1990s, Paksi Képtár, Paks

Die Sammlung 2 / The Collection 2, 21er Haus, Vienna

2012

Ça & Là / This & There, Fondation Ricard, Paris

Montag ist erst übermorgen, Akademie der bildenden Künste, Vienna

Gallery by Night, Stúdió Galéria, Budapest

Bleibende Werte? /Enduring Value?, Kunsthaus, Bregenz

Demnächst, Galerie 5020, Salzburg

Die Sammlung / The Collection, 21er Haus, Vienna

State of Affairs, amt _ project, Bratislava

2011

Erschaute Bauten / Envisioned Buildings, MAK, Vienna

Beziehungsarbeit, Künstlerhaus, Vienna

Monument Valley – Jaegerspris Revisited, UFO presents, Berlin

5x5 2011, Espai d´art contemporani de Castelló, Castelló (Spain)

Shift and Flow, Dorsky Gallery Curatorial Programs, New York

alter///scrinium – Ten Theses of Architecture, 9th International Film Festival, Vladivostok

In Between, Austria Contemporary, CAC, Vilnius

Magáért beszél, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest

Where is my Place, Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, Venice

Passion of an Ornithologist. On Myth Making, BWA Sokol, Nowy Sacz (Poland)

NeoSI #2: neue Situationistische Inter......nationale, Kunstraum Schattendorf (Austria)

Public Folklore, Grazer Kunstverein, Graz

2010

Related Spaces, Ernst Museum, Budapest

There has been no Future, there will be no Past, ISCP, New York

Architecture and Context – Breuer in Pécs, Fuga – Budapest Center of Architecture, Budapest

La Ciudad Interpretada, Public Space/CGAC, Santiago de Compostela

Paisatge. Paisatge?, Angels Barcelona

Over the Counter, Mücsarnok, Budapest

Le présent du passé, FRAC des Pays de la Loire, Gétigné-Clisson

Unmistakable Sentences, Ludwig Museum, Budapest

Transitland, Space Gallery, Bratislava

Art Always has its Consequences, (former) Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb

Arrivals and Departures_Europe, Mole Vanvitelliana, Ancona

A Pair of Left Shoes, MSU – Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb

Fine Line, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna

2009

TypoPass, Labor, Budapest

History, Memory, Identity, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Modena

BC 21 Art Award, Augarten Contemporary, Vienna

A Pair of Left Shoes, Kunstmuseum Bochum, Bochum

Új szerzemények – rég nem látott művek, Ludwig Museum, Budapest

Reduction&Suspense, Magazin4 – Bregenzer Kunstverein, Bregenz

El Pasado en el Presente, Laboral Centro de Arte, Gijon

Reading the City, ev+a Exhibition of Visual Art, Limerick

Fifty Fifty, Wien Museum Karlsplatz, Vienna

Figure/Ground, Transit, Mechelen

Rewind, Fast Forward – Video Art from the Collection, Neue Galerie, Graz

Expanded Box – Cinema, ARCO, Madrid

2008

Moirés, Kunstraum der Universität Lüneburg, Lüneburg

Colección Pecar. Atemporalidad, Museo de Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo, Santander

In Between, Austria Contemporary, Genia Schreiber University Art Gallery, Tel Aviv

Modern Ruin, Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane

6th International Biennale, Gyumri (Armenia)

Art Unlimited, Art 39 Basel

50, Studio Galeria, Budapest

Islands+Ghettos, Heidelberger Kunstverein

Scene Missing, Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna

Scene Missing, Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin

Phantasies of the Beginning, Billboard Gallery, Bratislava

Undiszipliniert, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna

Am Puls der Stadt – 2000 Jahre Karlsplatz, Wien Museum Karlsplatz, Vienna

2007

Cine y casi cine, Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid

Kapitaler Glanz, Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf

Models for Tomorrow: Cologne, European Kunsthalle, Cologne

2006

This Land is my Land, NGBK, Berlin

Center, MAK Center, Los Angeles

wood, photographs, aluminium plate, LED, table, book, silkscreen, personal computer, monitor, web connection, nivea cream, video, paper, graphite, pencil, acrylic, Galerie Jocelyn Wolff, Paris

How to do Things?, Kunstraum Kreuzberg / Bethanien, Berlin

This Land is my Land, Kunsthalle Nürnberg, Nuremberg

Der Raum zwischen zwei Bildern, Fotohof, Salzburg

Geschichte(n) vor Ort, Volkertviertel, Vienna

How to do Things?, Trafó, Budapest

2005

Re:Modern, Künstlerhaus, Vienna

Brutal Ornamental, Galerie Kosak Hall, Vienna

Reading in Absence, Trafó, Budapest

Utopie : Freiheit, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna

Alice Creischer/Andreas Siekmann, Andreas Fogarasi, Dorit Margreiter, Kunstraum Lakeside, Klagenfurt (permanent)

Storyboards – Trapped in the escape, Vector Gallery, Iași (Rumania)

citysellingcitytelling, Sparwasser HQ, Berlin

2004

Images of Violence/Violence of Images, Biennale of Young Artists, Bucharest

Living Room, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna

Wiener Linien, Wien Museum Karlsplatz, Vienna

Video as Urban Condition, Austrian Cultural Forum, London

Formate – (re-)constructing the city, Galeria Noua, Bukarest

2003

Gegeben sind... Konstruktion und Situation, Galerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck

Balkan Konsulat proudly presents: Budapest, Rotor, Graz

GNS, Palais de Tokyo, Paris

Gravitation, Moszkva tér, Budapest

Grosser Sommer an der Thaya, Drosendorf

2002

Site-Seeing: Disneyfication of Cities?, Künstlerhaus, Vienna

Evidence, Essor Gallery Project Space, London

Manifesta 4, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt/Main

Double Bind, ATA Center for Contemporary Art, Sofia

Gallery by Night, Stúdió Galéria, Budapest

2001

Szerviz, Mücsarnok/Kunsthalle, Budapest

Real presence, Studentski Kulturni Centar, Belgrade

A table, an office, a building..., Semperdepot, Vienna

January Show, Passagegalerie Künstlerhaus, Vienna

2000

block, Apex Art, New York

99/00, Semperdepot, Vienna

1998

Clarice Works, Zentnerstrasse 18, Munich

1997

Új stúdiósok, Duna Galéria, Budapest

1995

Odyssee today, University of Athens, Athens

Odyssee today, Depot, Vienna

Inquiry

Please leave your message below.