—

Dario Wokurka

Unexpected Paintings

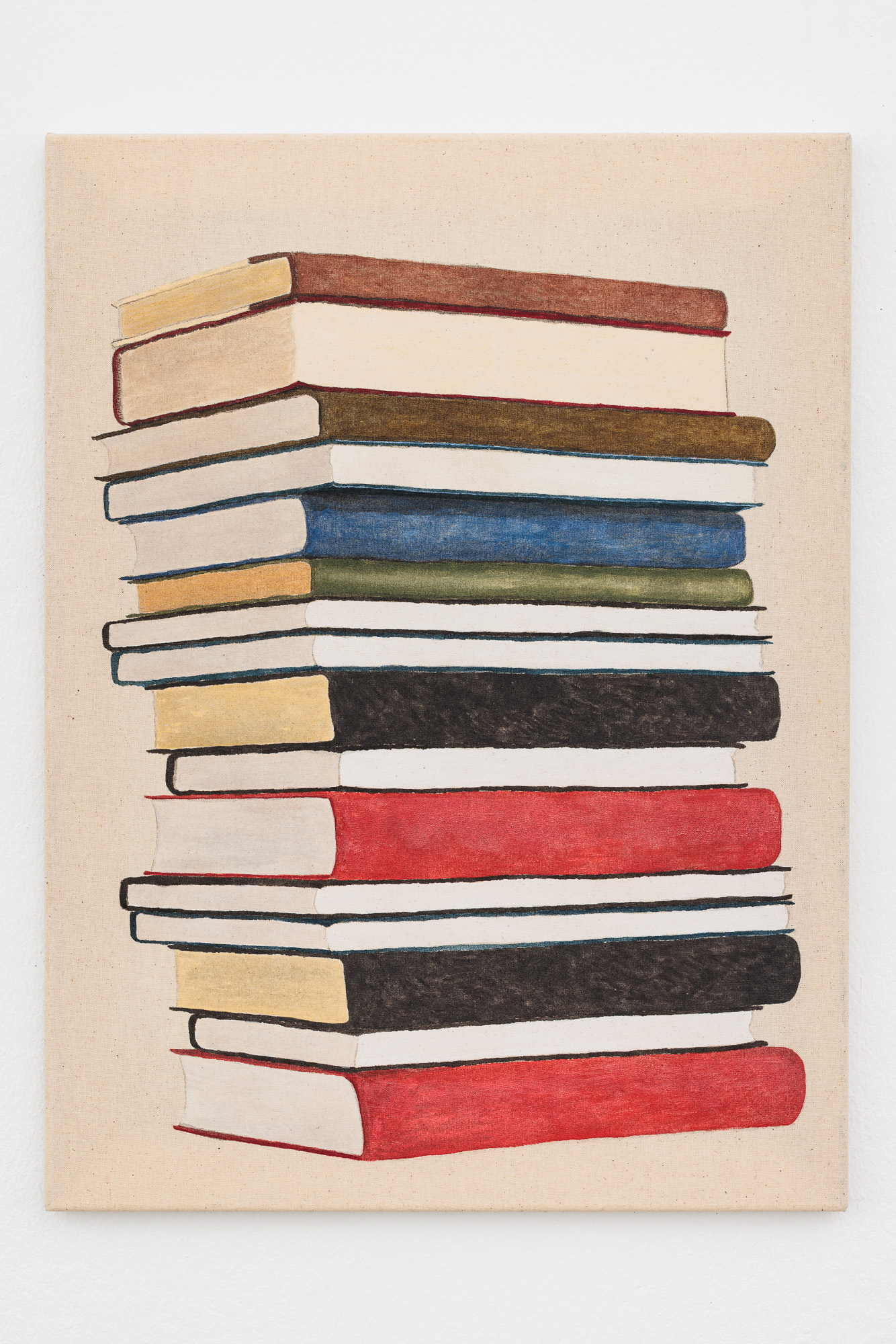

While we are on the phone, we are scrolling through the Dropbox folder with the selection for the exhibition from bottom to top like through a pile of books and I indeed say that our conversation about the book cover of the English translation of Pierre Bayard, whose mischievous advice cringe you casually translate into a communication theory of painting, could be the starting point for my writing and I have to smile when you say the title Books One Hasn’t Read (How to Talk). As we are now talking about pictures that I do not know if I have seen before because I do not have Wi-Fi here or because you have already uploaded an updated version or because I saw a different but very similar picture as a watercolour in your studio a year ago and this performance of speaking-about in the gauging and constant game of concealment and ultimately the modest revelation of one’s own lack of information, just as you press the record button and we are talking now and how the performative character of speaking about these pictures is now becoming so reflexive for me, you say: By the way, maybe a bit too much information, but still okay if one knows it. At least I told you.

The question of which information goes into the text, and which does not, already reflects in its structure the question of which information the beholder’s gaze extracts from the pictures or what prior knowledge is imposed upon them to have. (And how informed writing could contribute to this.) Because these pictures always emerge in reference to an implicit knowledge that lies in the beholder’s gaze, just as every interpretation is always fed by the knowledge that we have gained, among other things, from other perusals.

Regarding the role of the beholder’s involvement in the construction of meaning in your pictures, you say: the informed gaze and at the same time that you do not know whether anyone has already coined this term (whether one has read it like this or something similar before) and I, on the other hand, suggested the term incomplete reading because knowledge of all references can never be taken for granted.

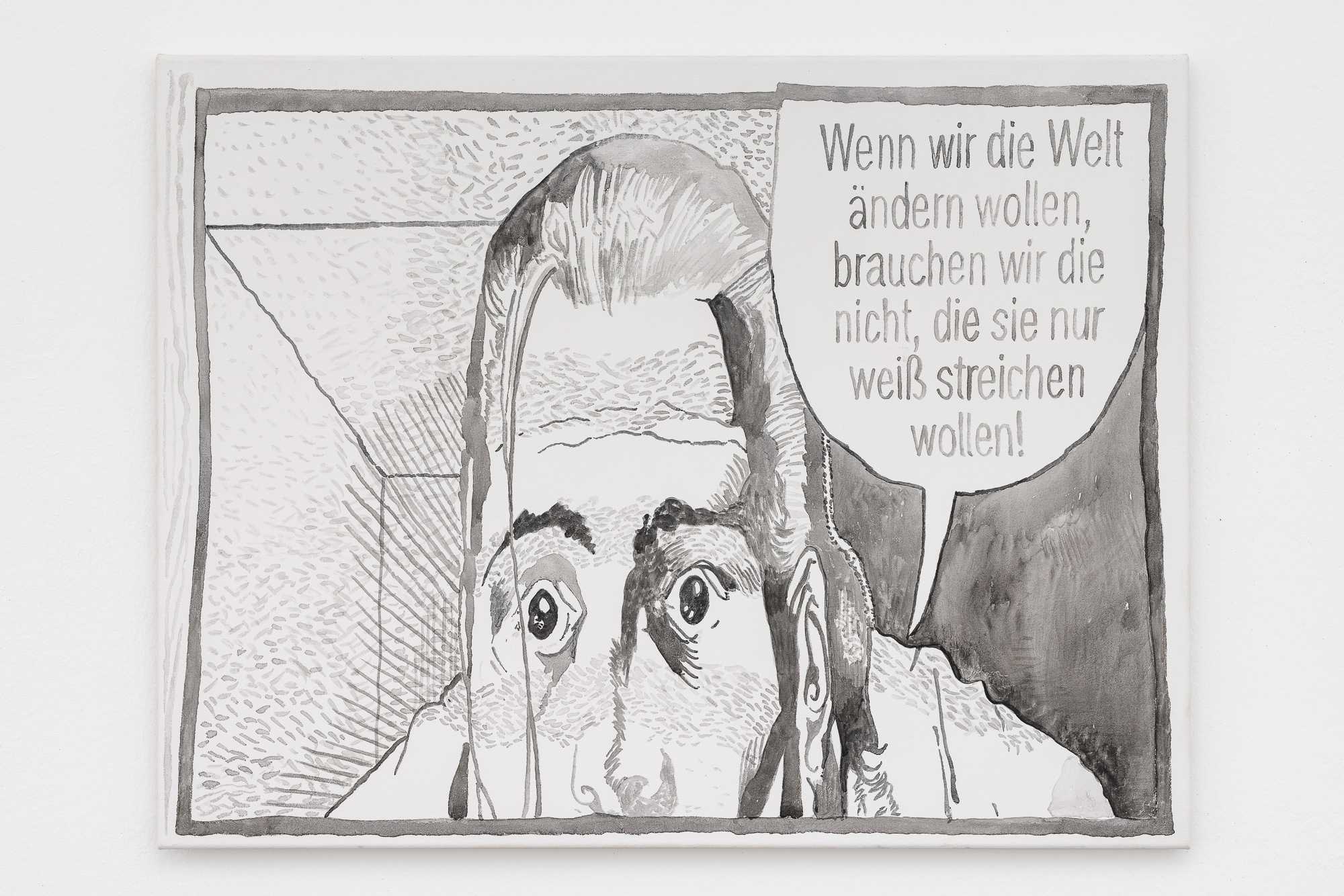

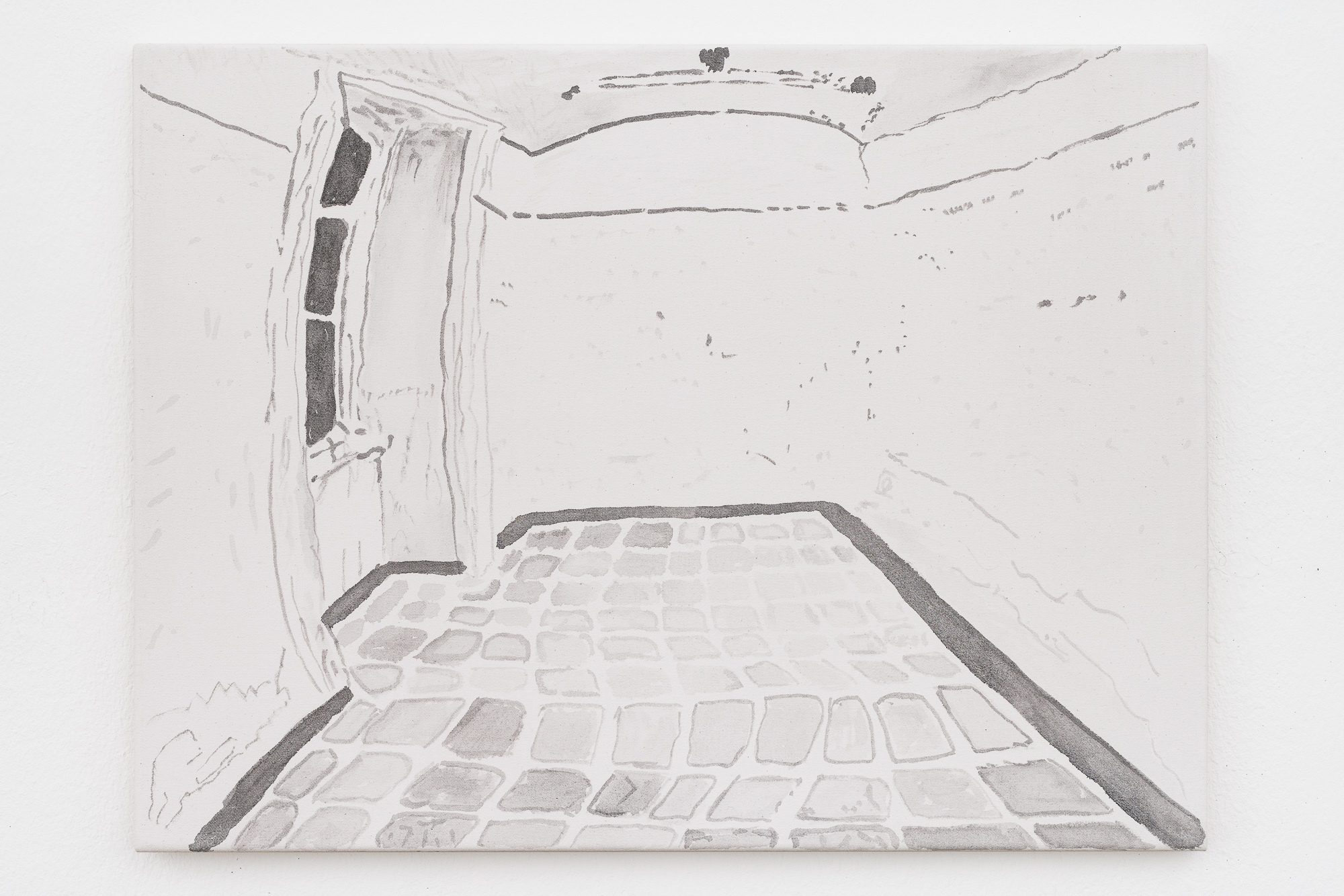

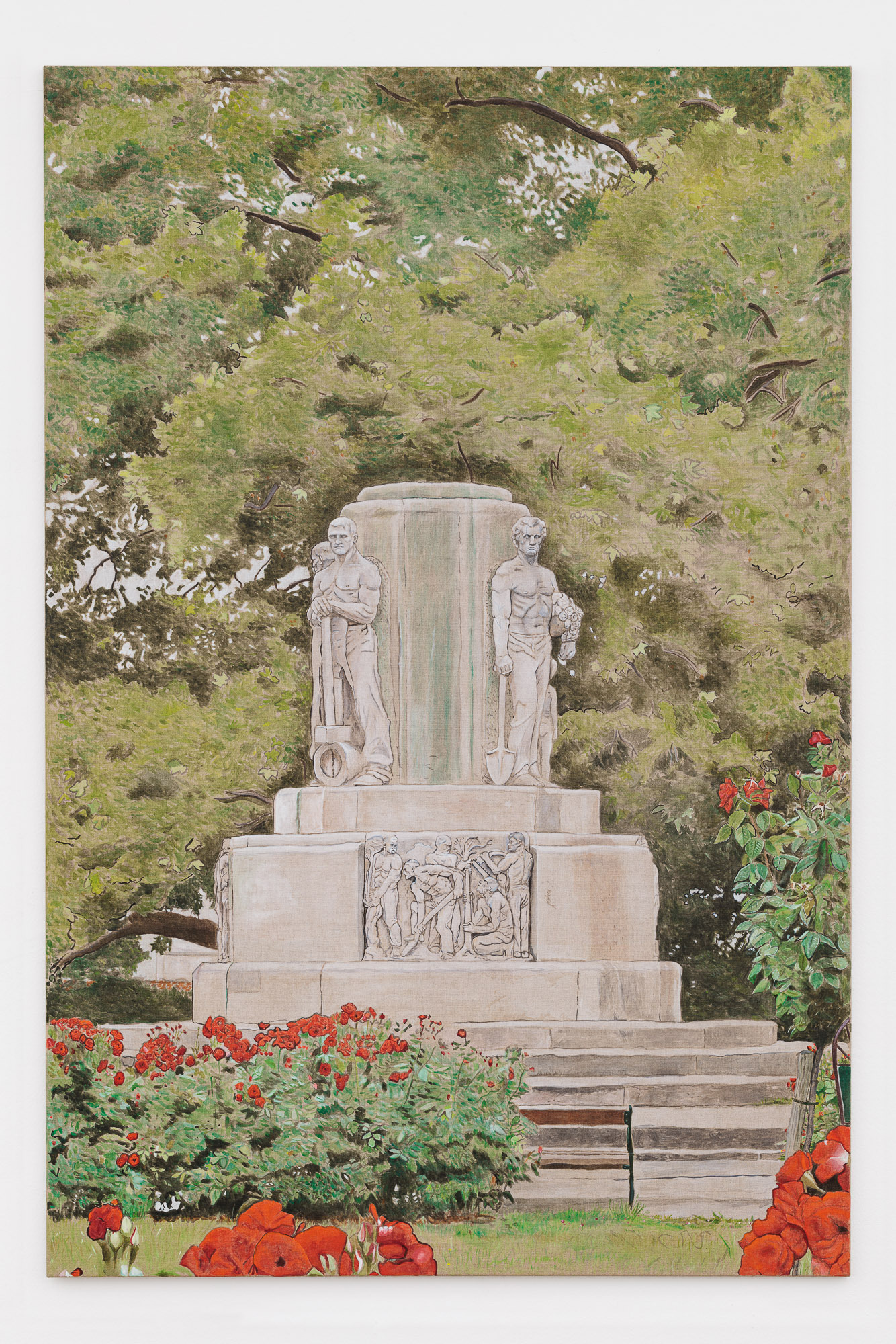

Proposal/Platz der Arbeit formulates a proposal for a critical redesign of the monument to a rather contentious and antisemitic mayor. You were not invited to the competition for the redesign, to which you present an independent painting in response. And I understand the necessity of the medium, namely in the reality-constructing validity claim of painting itself, where it takes the place of material reality, respectively, supersedes it.

Impossible anamnesis: I map in my mind where I saw the monument from, we talk about the coffee house (did we meet there once?). I connect, I try to fill in the blanks and fail.

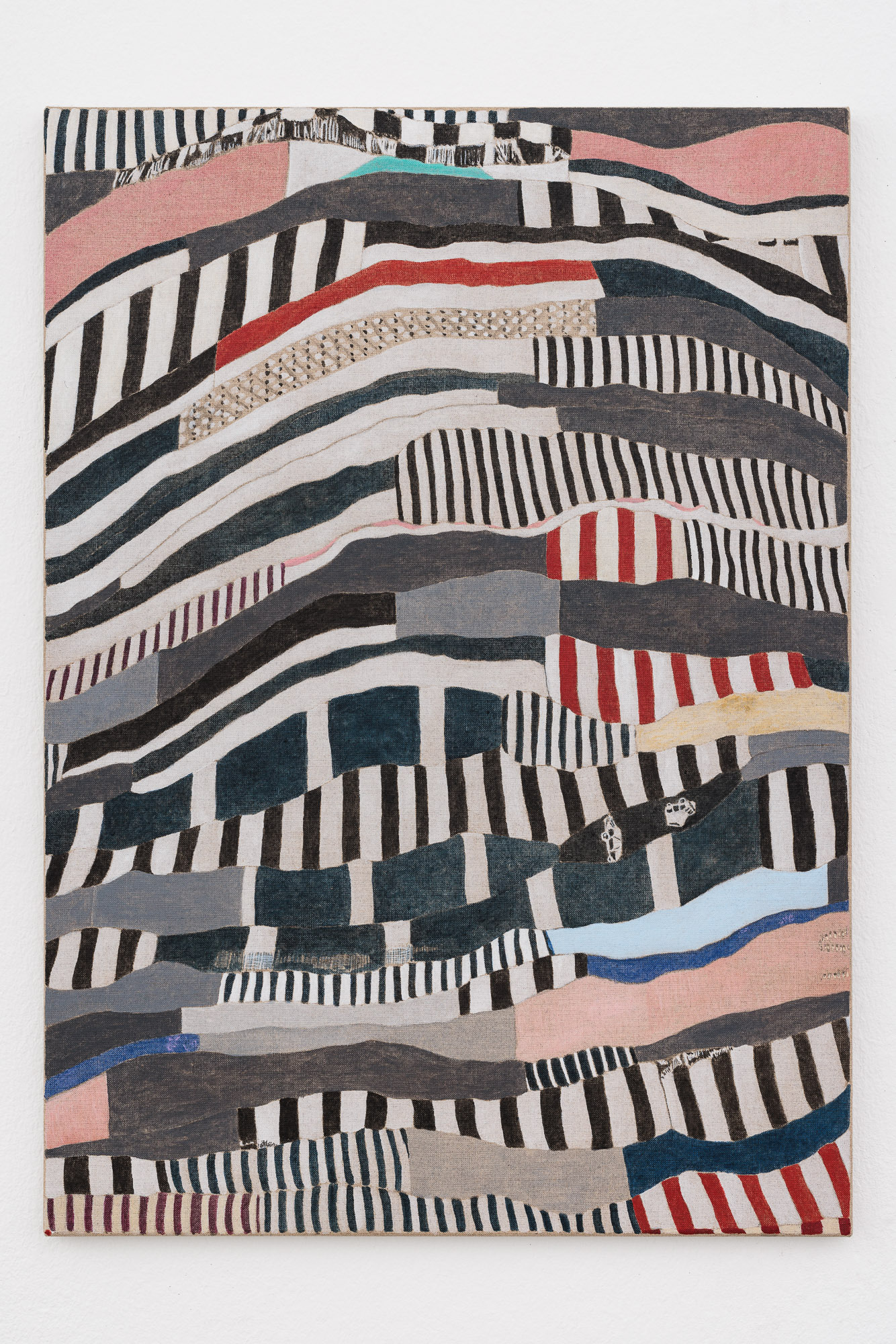

But I am quite sure that the Improvement of Central Europe that we are now talking about on the phone while conversing about the pictures for the exhibition was lying on your kitchen table in the fifteenth district a year ago. At that time, you were working on a series about carpets, the products of which you have now translated into painting. Because I have been following your work for a while, it is easier for me to recognize the auto-referential moments that occur in your work.

In addition to the self-references, the external references are even more visible:

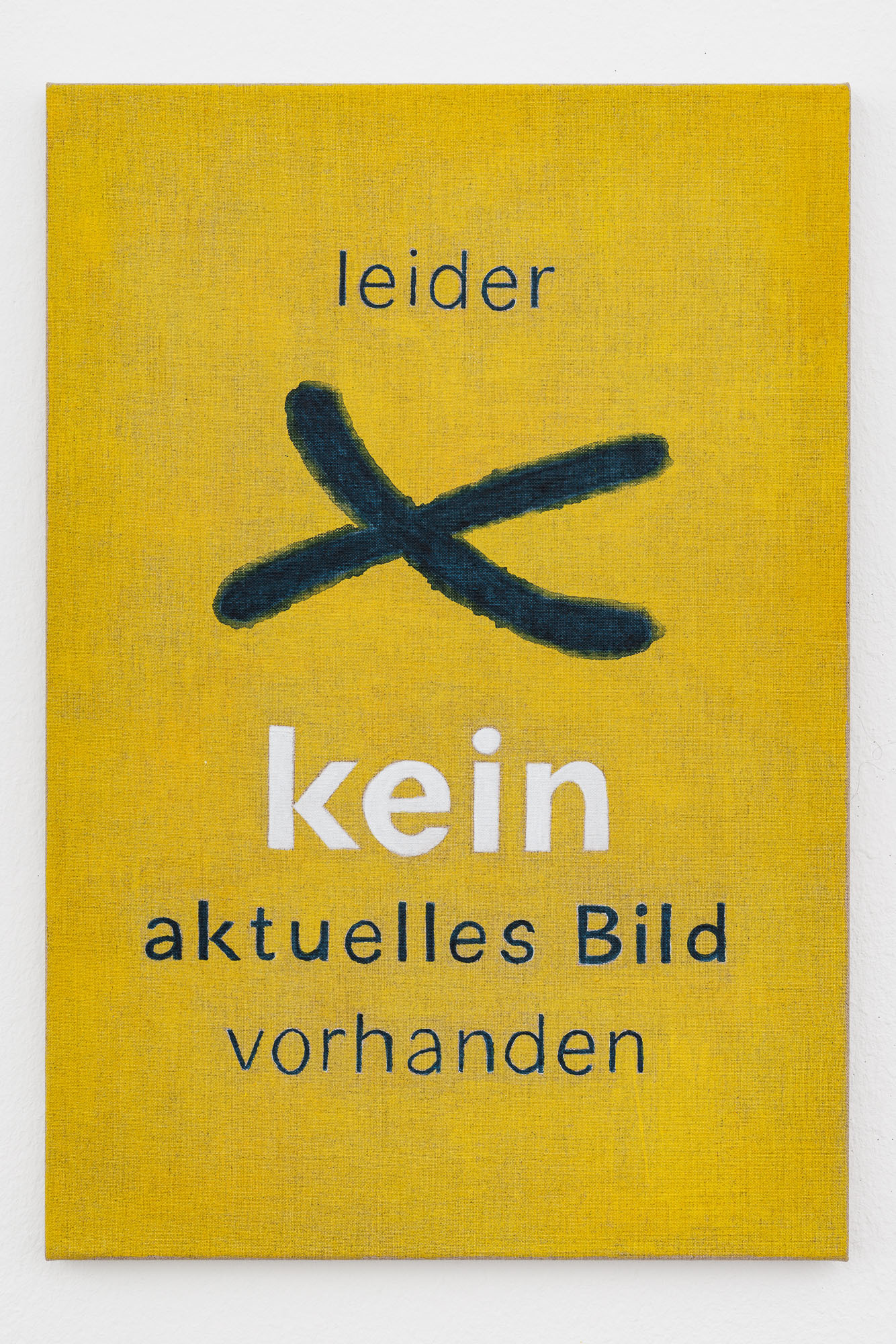

Even for the outside (meaning the less) informed gaze (about the entire work), references from the history of painting, but also extra-pictorial references such as graphic elements from digital image processing, scaling, viewing habits from social media, etc., mark your interest in painting as an act of translation.

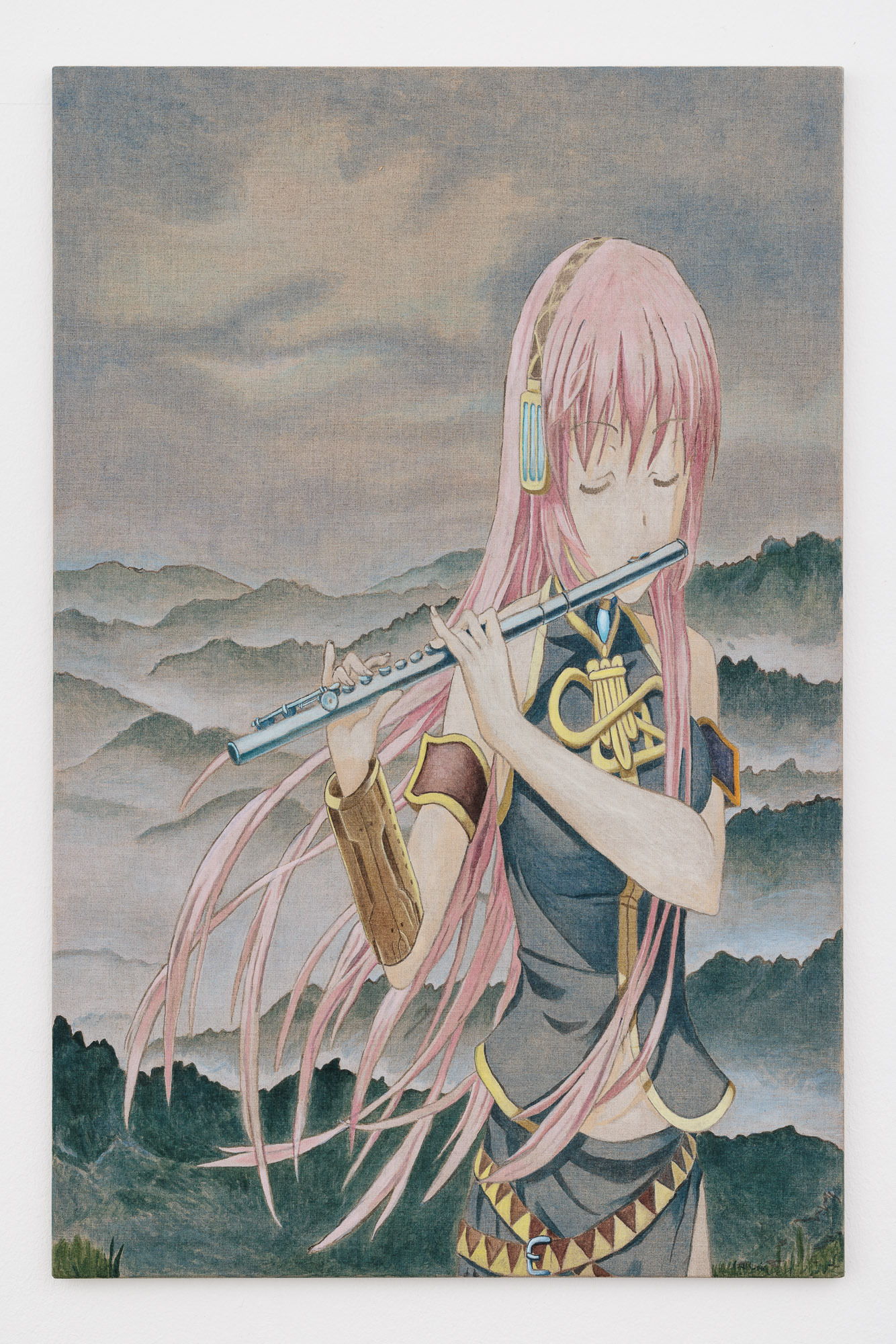

The poetic surplus value is particularly interesting when something is transferred from one system into a new system that cannot actually operate with it (the digital into the analogue) or the translation from a system where there is no direct access to historical understanding, like the Chinese scholar painting of the 18th century to my Western thinking about art history, which always primarily uses modernism as a tool for reasoning.

Now my screen has gone black too, you say.

Yet another surprise.

My commenting on art also repeatedly wants to recite negation as a basic figure of modernism. Obviously: surprise is the negation of expectation, is the category of the new, which becomes, as it were, the sole thing that can be expected in art. We have both read this Groys book, or at least that is how we remember it.

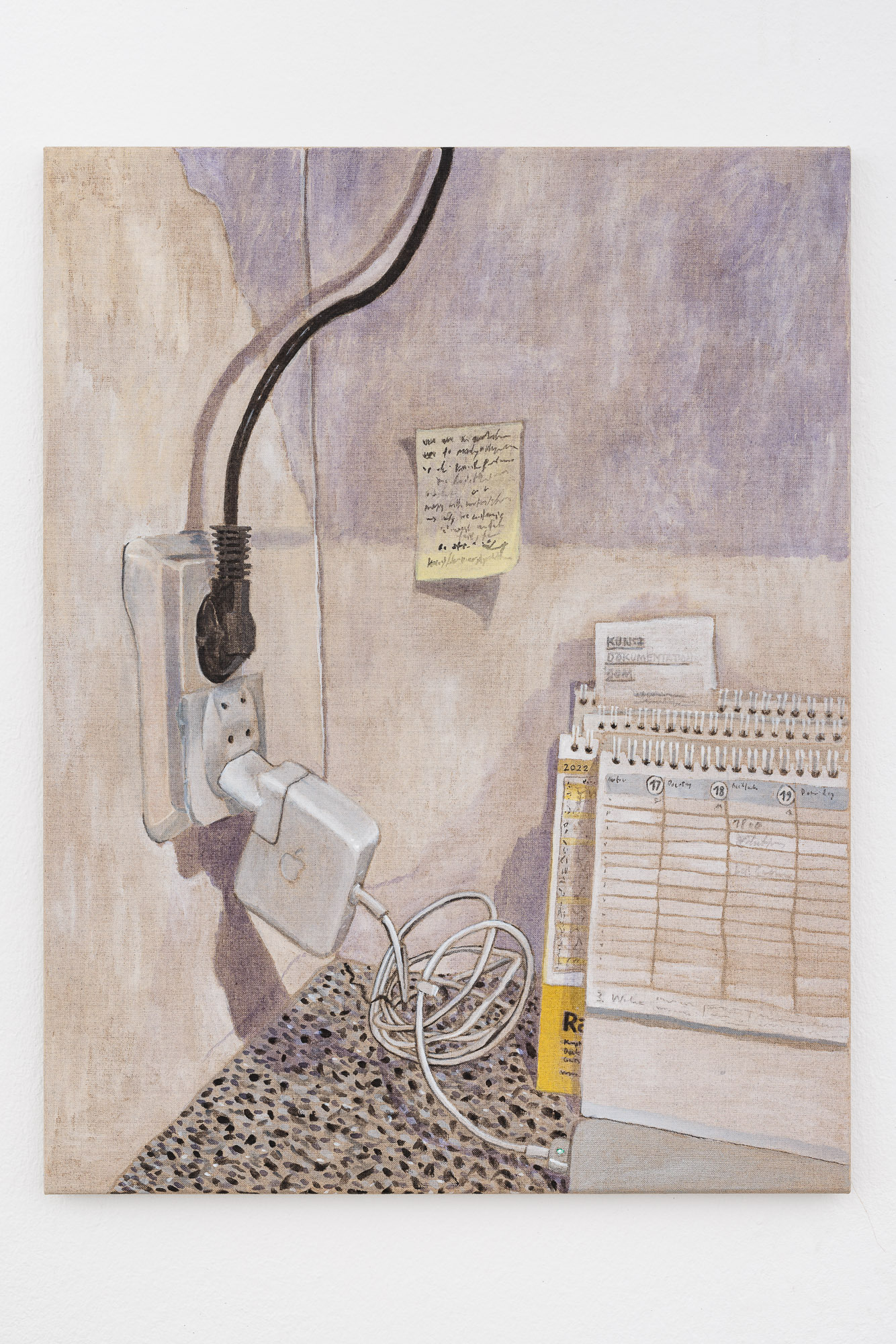

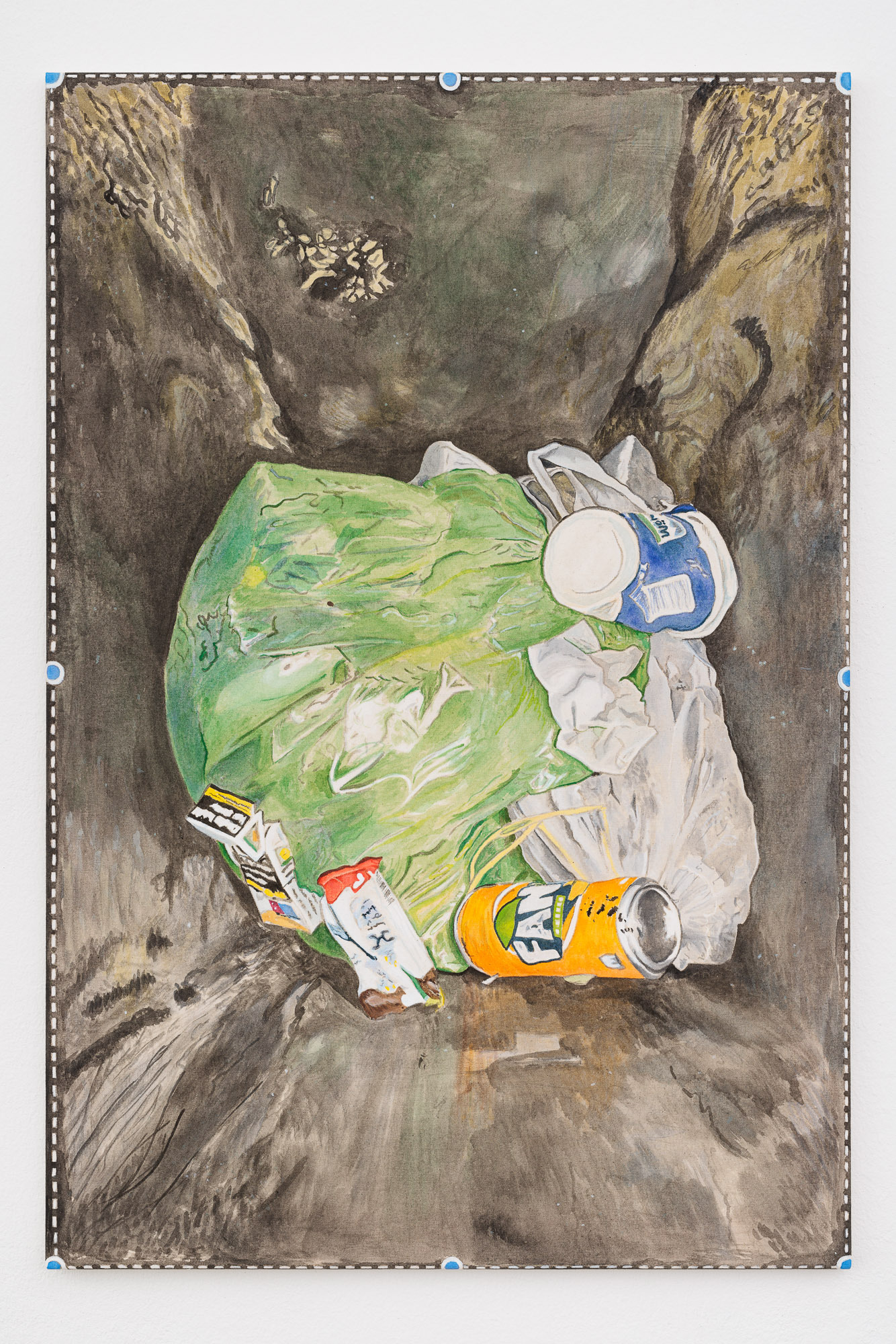

In any case, not to be confused with commodity form; I am thinking here of the quodlibet tradition in Dutch genre painting, where one certainly wanted to demonstrate the mimetic power of painting as something sellable and depicted everyday objects in life size.

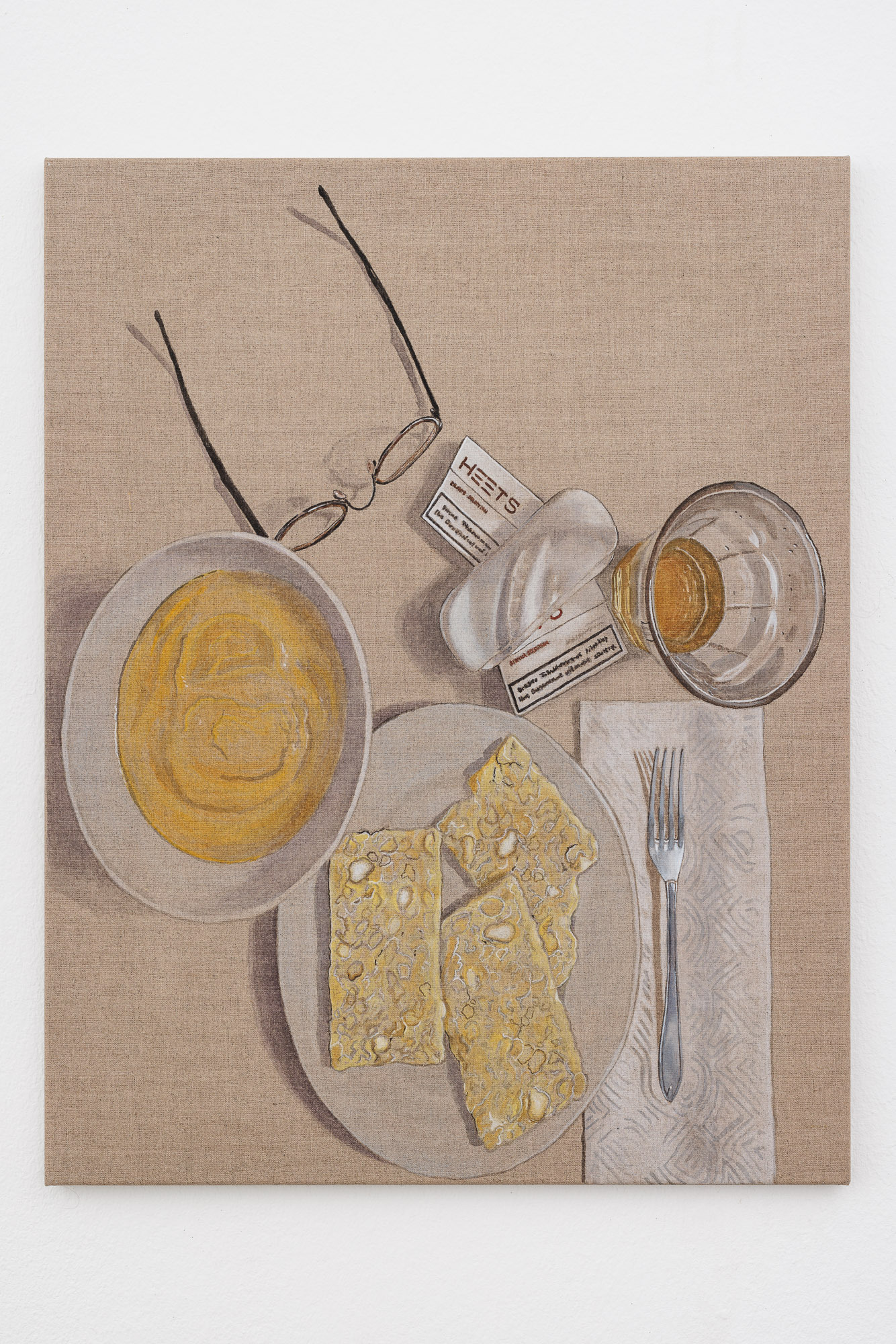

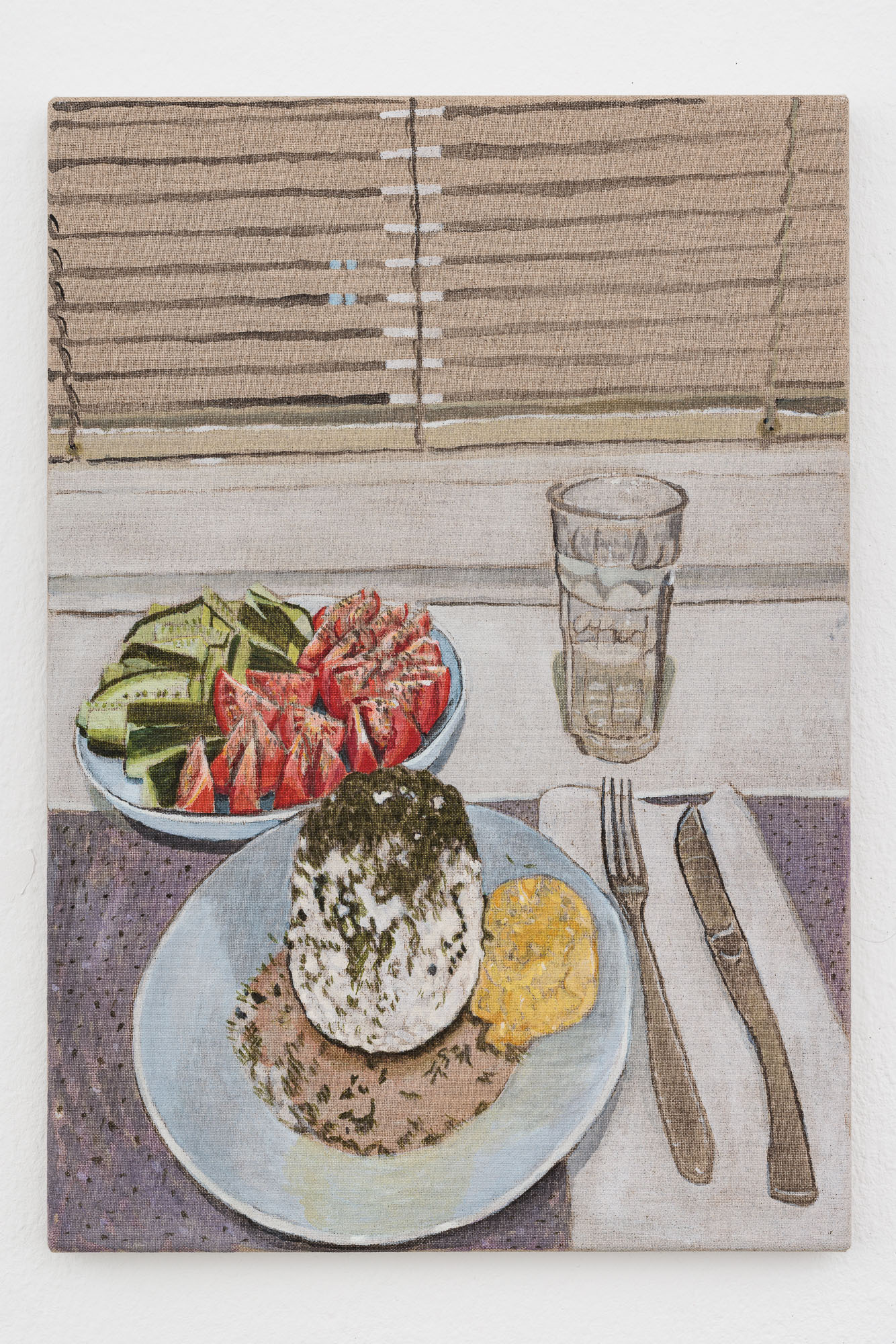

Your still life with grey cheese, apple sauce, e-cigarette: the lean cheese depicted in lean painting, because you do not paint with oils, but dilute acrylic paint with water, and I see in this a humorous reference to the discourse about the fact that in modernism the material, rather than the content, has become primary. And that painting is committed to depicting its own means and conditions of production, as in the picture with the ducks, where the possibility of the colour used is exemplified through a greyscale.

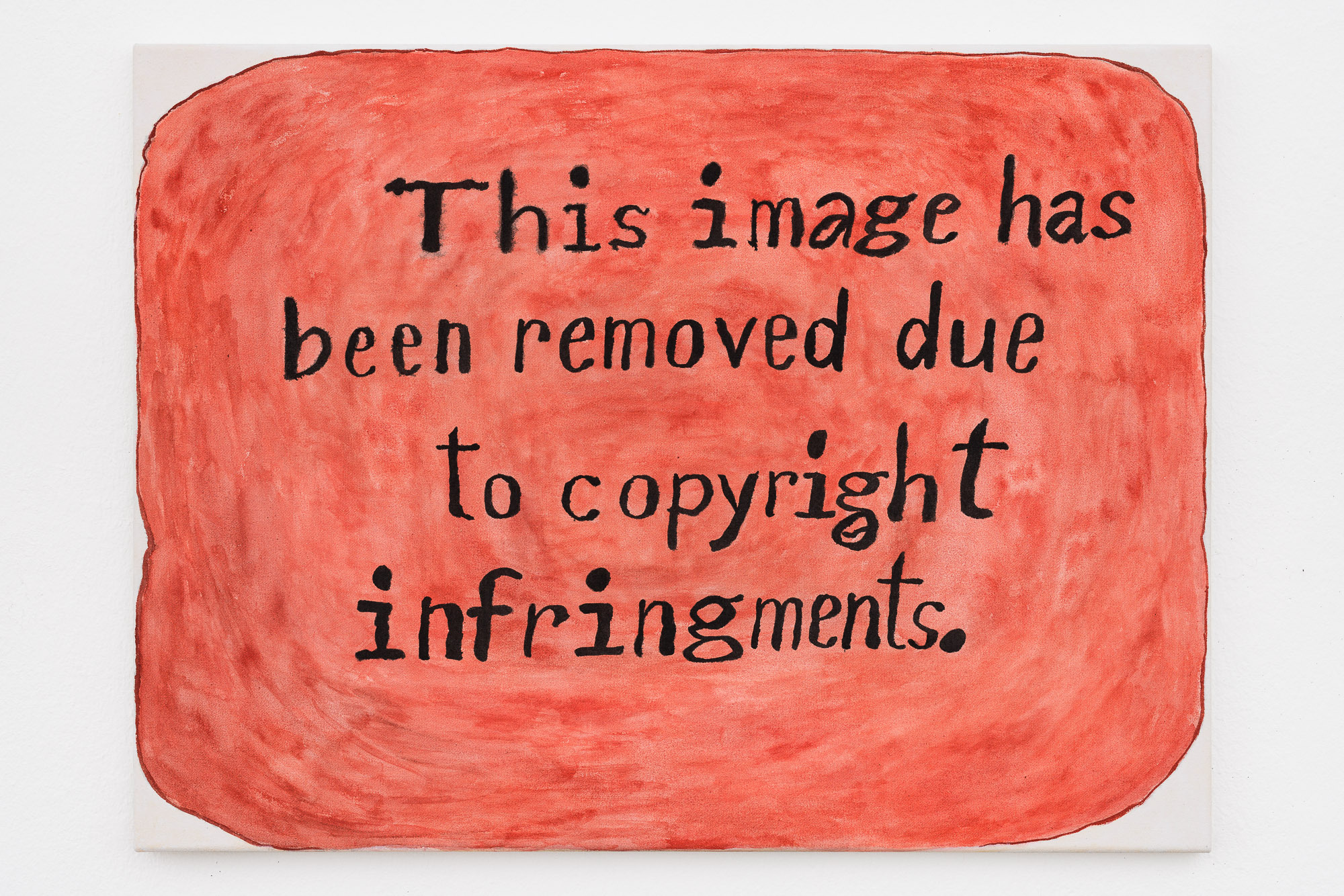

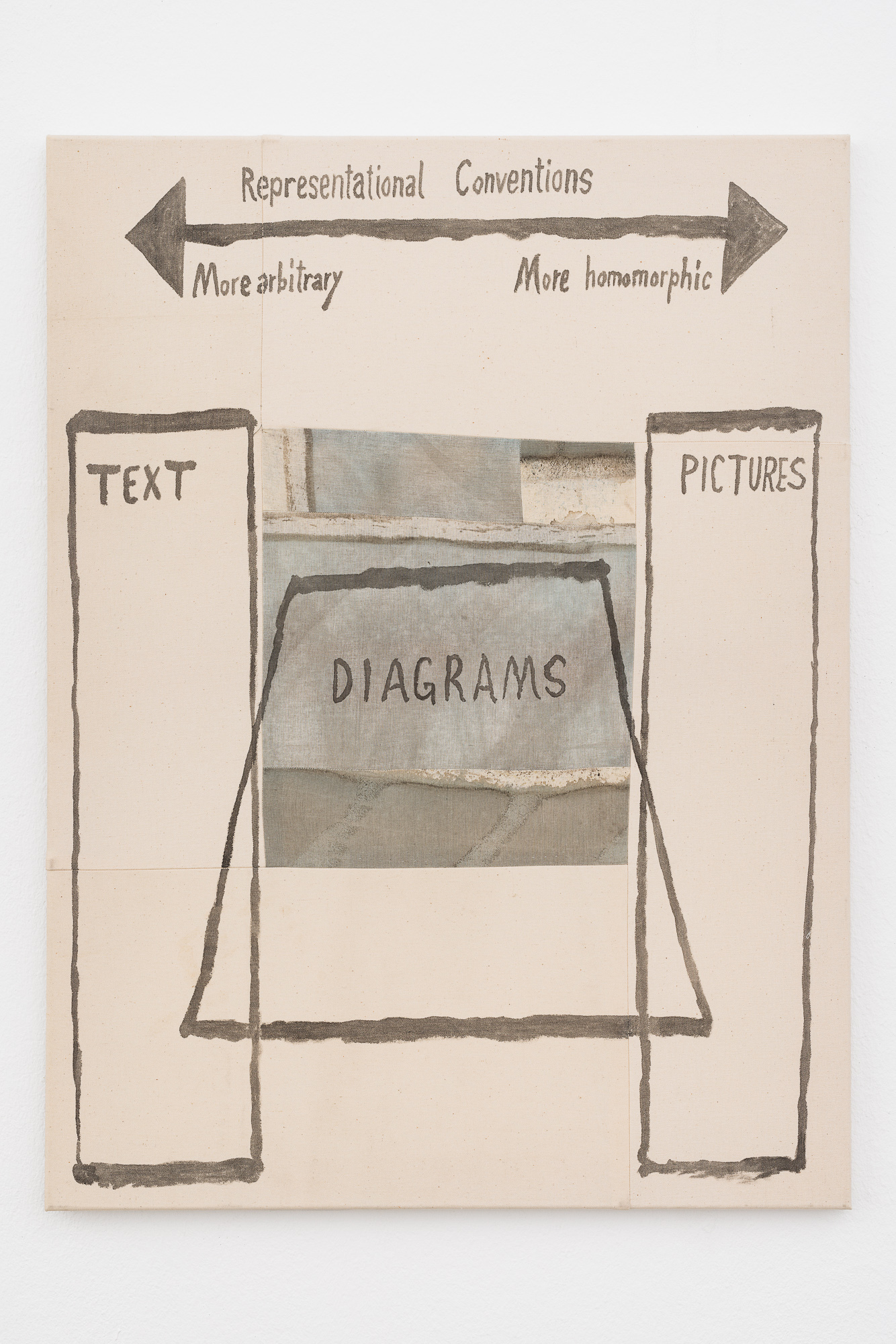

The paintings also reflect their medium in that they sometimes test different ideas of what a picture is or could be. The communicated refusal of information that already constitutes information, brushstrokes made of water, a diagram about diagrams.

The self-reference is also the maximum limitation, modest like lean cheese. But rich in the achievement that seeing itself becomes the object of seeing. And the fact that a total wealth of thought about pictures opens up in this modest reduction is the surprise when seeing.

One does not have to know the specifics of the references to understand the referential character of the pictures. (And, in that respect, they are also scholar paintings to me, that is how I understand the term, and you say that is a conceptual misunderstanding on my part, but something which you could relate to.)

This is not about the discourse of copy and original, because access to the original has been lost for ages, because everything has always been a copy (painting) or sampled and distorted beyond recognition like a Nightcore track.

The crucial point: sapienti sat, but doesn’t have to, the pictures work anyway.

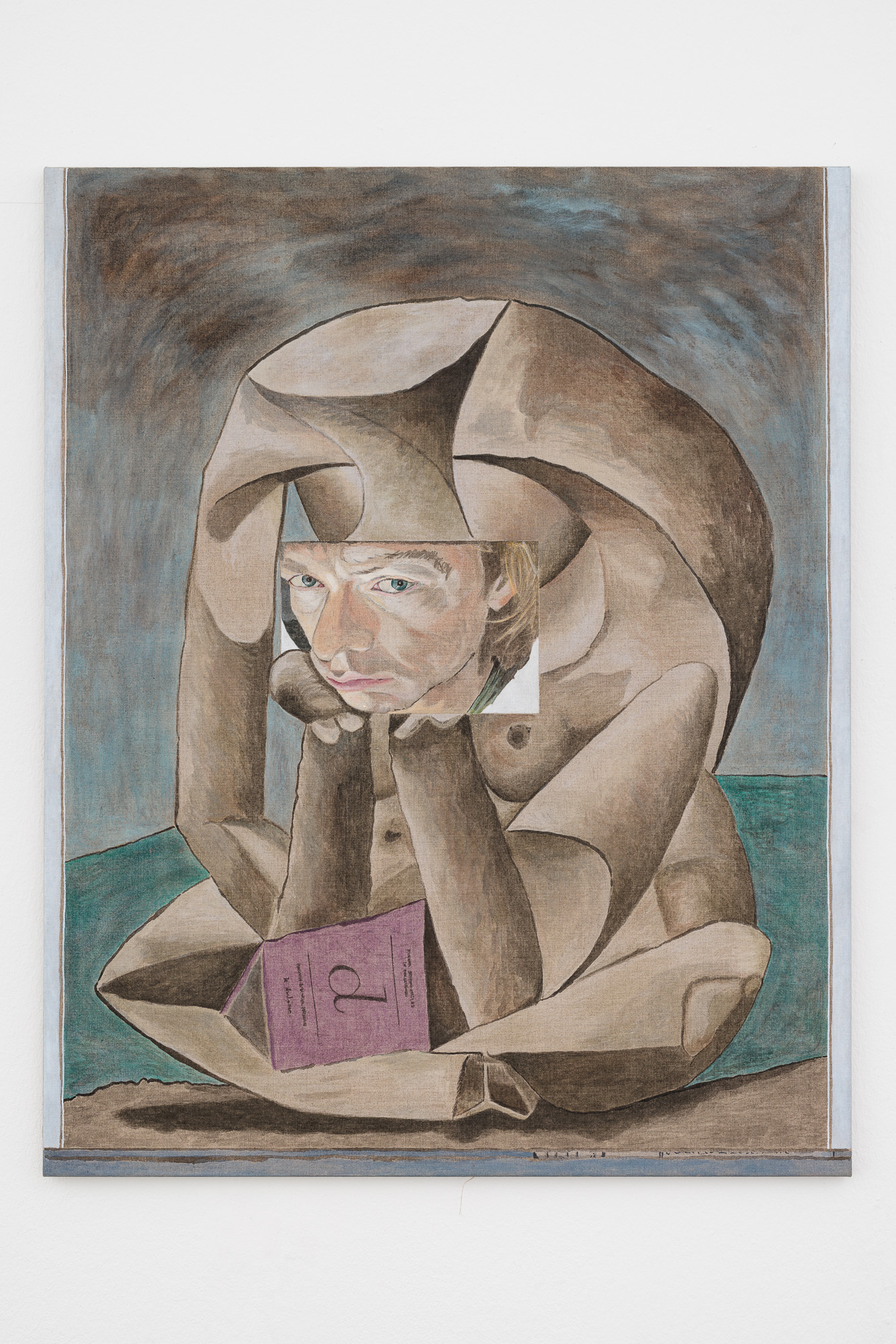

Then you look at me from the painted InDesign interface. Self Portrait as a Melancholic Maiden. The concept of melancholy, dandyism, and its gendered readings do not have to be mentioned explicitly, but they could.

I say, of course I will include one or two associations, and I name a title by Agamben that I have actually read. The gaze is the medium of melancholic desire in the early modern period, of the irrevocably absent that is an image. (Impossible Anamnesis.)

I understand that the reading of the pictures actually completes them. Therefore, everything is a misunderstanding and every misunderstanding makes sense, that is, creates meaning.

I find the communicative openness of your pictures tender and generous and not terse in the PoMo sense. One can never have read everything.

Then unhinging the usual logic of representation again when the references find their new starting point as something that can no longer be assigned.

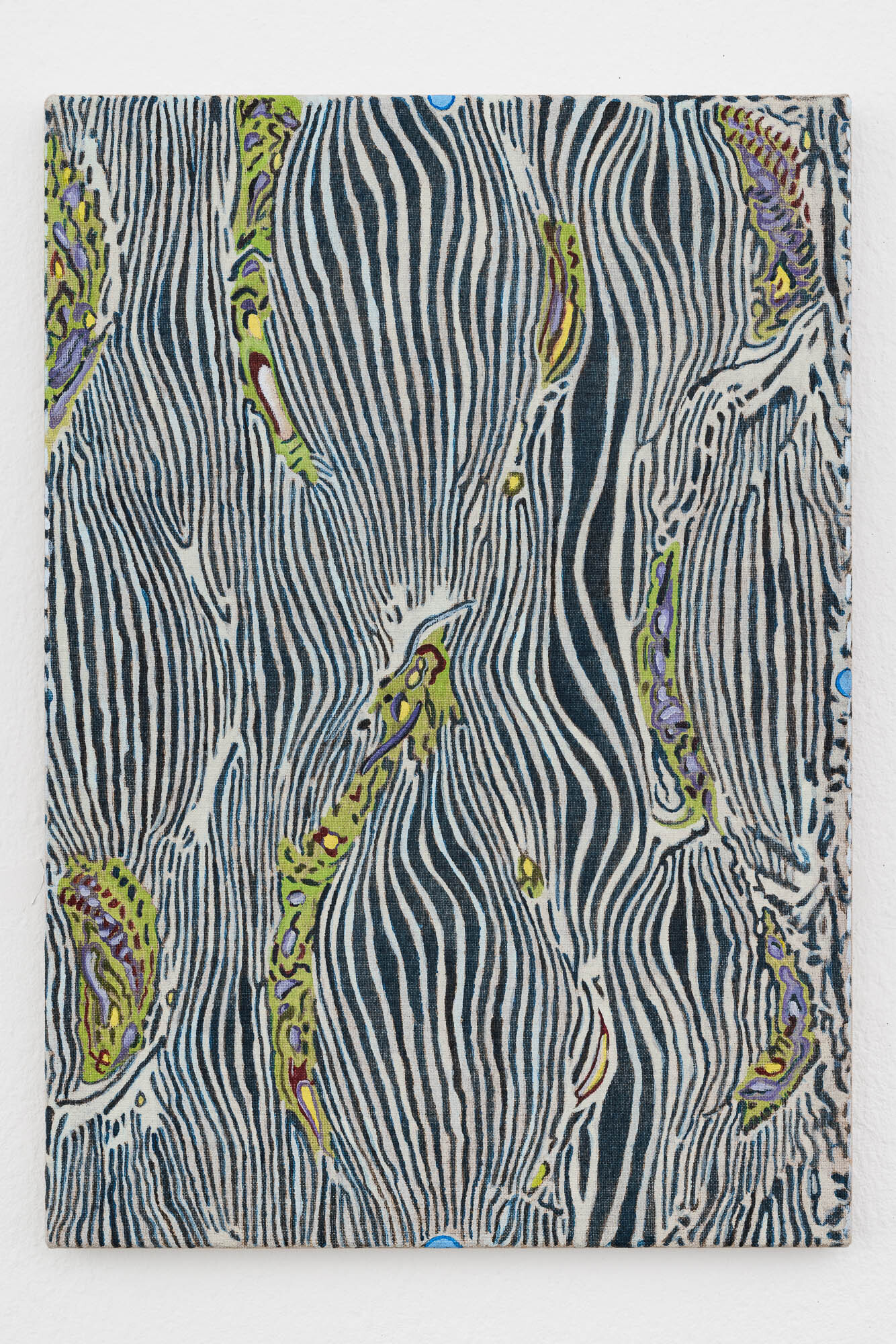

I find Untitled (Line Circles) defiant, but above all humorous. You photographed the fabric that gives the work its title, which the architectural firm Coop Himmelb(l)au made for Backhausen (a very prestigious and traditional textile company in Lower Austria associated with the Wiener Werkstätten), but you did not receive it. When the company had to close down, almost ten years later, you painted it.

After all, it was also a curtain with which Parrhasios defeated his rival Zeuxis in a painting competition, who, when he tried to push it aside— surprise—discovered that it was only painted.

It is the curtain that marks the origin of painting as its own reality, and ultimately also as a fabric in the autopoietic sense.

Untitled (RH Compressed), the painted fabric picture which, in the etymology of the text, refers to the context of meaning in the conveyance of information and the character of the work as a text that programs itself, as a chain of translations that inevitably co-produce misunderstandings and errors that are beautiful.

Then you talk about books that you have read several times already, but have now ordered again, and when we talk about cybernetics, you mention the book Nicht schon wieder...! of which, as you say, you always try to have at least two.

Sophia Eisenhut

(translated by Brian Dorsey)

Inquiry

Please leave your message below.